COVID-19 is transforming the lexicon of languages worldwide, but for Japanese the challenges are unique. What’s “overshoot?” Find out.

In the English-speaking world, a plethora of terms, some new, some not so new, have inundated people’s daily lives. “Lockdown,” “quarantine,” “hot zones,” “social distancing” and “flattening the curve” all have a familiar ring by now. In a matter of months, our vernacular has been rewritten. But what’s the impact on languages as divergent from English as, say, Japanese?

This head-spinning transformation of language is crazy enough in English and other western languages, but as you might expect, the situation gets even more dicey in Japanese. Let’s look at “pandemic” as an example.

The word “pandemic” has existed in English from around 1660-70; a combination of “pan” (common, public) and “demos” (the people). And as we all know by now, it refers to the worldwide spread of a new disease. Other western languages have equivalent counterparts that may be easily recognizable even if you don’t know that language, for example, “pandemia” in Spanish, “pandémie” in French, and “Pandemie” in German. Even the Russian “пандемия” which may look a little different, is actually “pandemiya” written using the Cyrillic alphabet.

Now pan over to Japan, and the situation is not nearly as simple. Run “pandemic” through Google Translate and you’ll get パンデミック, the transliterated term pronounced “pandemikku.” But if you’re Japanese, this only makes sense if you already know that term to begin with, and since most folks in Japan don’t know the term, news broadcasts need to constantly supplement it with a Japanese description such as 世界的大流行 (sekaiteki dairyuukou, meaning “worldwide epidemic”).

The same goes for other pandemic-related terminology as well. In Japan it’s necessary to go through a two-tier process of mentioning a loanword and then supplementing it in a way that is understandable to the average Japanese person. Here are some noteworthy examples.

Contents

What’s up with “lockdown”?

Rokkudaun (ロックダウン : lockdown) is often augmented with 都市封鎖 (toshifuusa, literally “city blockade”). This loanword especially needs help because when transliterated into Japanese, “lock, “rock” and “loc” (short for localization) all become ロック(rokku), so the average Japanese would be hard pressed to understand rokkudaun on its own without a supporting description. What’s more, phrasal verbs (combination of verb and preposition) like those with “down,” “up,” “in,” “out,” “on” and “off” are always tricky to translate since it’s rare that the same phrase would exist in both the source and target languages.

Enter Japanese soccer legend Kazuyoshi Miura, and we have a new “English” phrase that is used only in Japan. On his official blog BOA SORTE KAZU, he urged the Japanese public to man-up and, in the absence of a government-imposed lockdown, to do a voluntary セルフ・ロックダウン (self-lockdown). Hashtag #セルフロックダウン

“Cluster” can’t stand alone

Kurasutaa (クラスター : cluster) has to be followed up with 集団感染 (shuudan kansen, literally “group infection”) or other supporting text to make sense, but it has gained a strong position as part of the official lingo for this pandemic. Visit the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare website and you may notice a link to a nationwide cluster map (全国クラスターマップ) to identify potential hotspots.

“Overshoot” gets a new spin

Oobaashuuto (オーバーシュート : overshoot) has also become a familiar term at COVID-19 briefings offered by the government. “Overshoot?” As in when you overshoot the freeway exit and have to go that extra mile for the next offramp? Or when a plane overshoots the runway and winds up in a very bad situation? Well, it’s the same word but used in an entirely new context that seems unique to Japan.

According to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “overshoot” refers to an explosive rise in cases where the number of patients doubles in two or three days, thereby exceeding or “overshooting” hospital capacity. This term entered the Japanese lexicon and has since gone viral (pun intended) after being used by Dr. Shigeru Omi, President of the Japan Community Health Care Organization and Vice Chair of the Novel Coronavirus Expert Meeting, presumably in the context of control theory, where “overshoot” refers to an output exceeding its steady-state value.

Meanwhile, Japanese networks also use 感染爆発 (kansen bakuhatsu, literally “infection explosion”) as a term that’s easier for the average citizen to visualize in the mind.

Japanese people today would be surprised to learn that the English term “overshoot” has no pandemic relevance in the English speaking world. But then again, it’s not much different from “salary man” (meaning “office worker”), “free size” (meaning “one size fits all”) and “baby car” (for “pram,” “baby carriage” or “stroller”) not being understandable to Anglophones either.

Soosharu disutansu (ソーシャルディスタンス : social distance) may be supplemented with 社会的距離 (a literal translation), but neither the loanword nor the Japanese phrase make much sense without context. So supporting text like人との距離を保とう (maintain distance between people) is used to help convey the message, but most people have only a vague idea of what it really means. Perhaps the hashtag #KeepDistance is more effective for a Japanese audience as in this graphic featuring Kumamon, the mascot character of Kumamoto Prefecture.

Two simple words, one serious message

Sutei hoomu (ステイホーム : stay home) is about as straightforward as you can get. Nothing fancy like “shelter in place” which is actually a relic from the cold war and also difficult to understand. Just plain ol’ “stay home.”

The supplementary Japanese phrase is 外出自粛 (gaishutsu jishuku for “refrain from going out”). The government of Tokyo has made a major push for this through social media using the hashtags #StayHome and #ウチで過ごそう (literally “spend time at home”), with Governor Yuriko Koike appearing on the video channel of one of Japan’s most popular YouTubers, Hikakin, to drive home the message for the younger demographic. But just how seriously Japan’s young generation is taking the situation remains to be seen.

The label that didn’t stick

“COVID-19” never gained widespread acceptance in Japan. Other countries have eagerly adopted this term, not only because it’s the official name issued by the WHO but also because “COVID-19” (8 characters) is shorter and more efficient than “novel coronavirus” (16 characters + 1 space). The Japanese term for “novel coronavirus” is 新型コロナウイルス (9 characters), but the shortened version 新型コロナ (5 characters) has been embraced as the go-to term in Japan. Shortening “coronavirus” (コロナウイルス) to “corona” (コロナ) is linguistically bold, but quite common for a country that regularly shortens sandwich (サンドイッチ) to sand (サンド), and subscription (サブスクリプション) to subsc (サブスク).

In addition to loanwords, Japan needs to also deal with its fair share of native terms that have entered the spotlight like 飛沫感染 (himatsu kansen for “droplet infection”), 濃厚接触者 (noukou sesshokusha for “high-risk contact”), and 無症状感染者 (mushoujou kansensha for “asymptomatic infected person”).

San-mitsu and the Three Cs

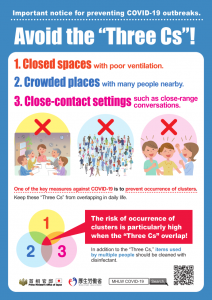

Amazingly, the Japanese key phrase “3密” (san-mitsu) that tells people to avoid Closed spaces with poor ventilation (密閉空間), Crowded places with many people nearby (密集場所), and Close-contact settings such as close-range conversations (密接場面), has been effectively translated into the “Three Cs” for foreigners who are either living in Japan or stuck there until flights resume. It’s not often that you get such a combination of natural source-target correlation and catchiness.

We should point out that the Japanese “Three Cs” is different from the “Three Cs” mentioned in western media, namely Clean (wash your hands), Cover (your mouth and nose when you sneeze) and Contain (the spread of the disease by staying home if you’re sick). In Japan, where hand-cleaning (with oshibori hand towels) and mouth-covering (with masks) was pretty much a part of pre-pandemic daily life, it’s only natural that the messaging has a different focus than the western world.

The language used in Japan as well as nations worldwide is going through a very abrupt transformation as society adopts new terminologies and adapts to new realities.

In a way, it feels ironic that the word “virus” is finally getting more traction in its original sense, as an ultramicroscopic infectious agent that replicates within the cells of living hosts, rather than its digital manifestation of computer-infecting self-replicating code. Surely this is not because there has been a drop in computer virus infections, but because the collective consciousness of everybody has shifted to the life-threatening disease.

We are living through a unique point in history. COVID-19 is bound to leave its mark on language, long after the novel coronavirus loses its novelty and becomes a chapter in the history books. It is our sincere hope that the worst of this pandemic will soon be over, and we’ll be able to look back on the year 2020 from a safe vantage point with 20/20 vision.

Douglass McGowan