*For audio recording purposes, some parts of the blog may vary.

Let’s talk about “language resolution.” And no, not the “I’m going to learn a new language by the end of the year” type of resolution. More like the resolution of a picture or video image; how much detail is in the frame. Each language has its own “resolution” that can make translation either easy or a major challenge.

The inspiration for this blog post happened some five or six years ago at a language industry event in Tokyo. An expert on machine translation had just finished his presentation and was taking questions from the audience, including “Which is more difficult, translating from English to Japanese, or from Japanese to English?” His answer was, “Presumably English to Japanese is more difficult because Japanese uses three different character sets.”

To be fair, this lecturer wasn’t a linguist, so his observation came from a machine’s perspective. But for us linguists in the audience, this answer was not exactly on target. Because although there are indeed three character sets in Japanese, there also are clear rules for their usage. So neither a native Japanese linguist, nor a properly trained AI, should find this to be much of a problem. No, there was something else making this language pair challenging. But what was it?

Dissimilarity of the two languages? Well, yes, but that was too broad, too vague. What is the keyword that this dissimilarity hinges on? My background in visual products (video cameras and monitors) led me to the keyword “resolution.”

Each language contains a certain amount of information in its sentences, like the visual information contained in a picture. If the picture is high-resolution, it can be converted to a lower resolution without much problem. But if the picture is low-resolution to begin with, you can’t blow it up and expect a pretty result. The visual information just isn’t there. So you are faced with either having to use a pixelated image, or (if you’re lucky) apply advanced image processing where algorithms kick in to interpolate the missing information and increase image resolution. This is exactly what the human linguist does all the time.

Language resolution is always 100% for any monoglot who speaks that language natively. But when paired with another language, such as in translation when it becomes either the source or target language, the resolution disparity between the two becomes apparent. Translating from a high-resolution language to a low-resolution language usually is not problematic, but the difficulty ratchets up when translating from low-res to hi-res language.

Contents

A one, and a two, and a…

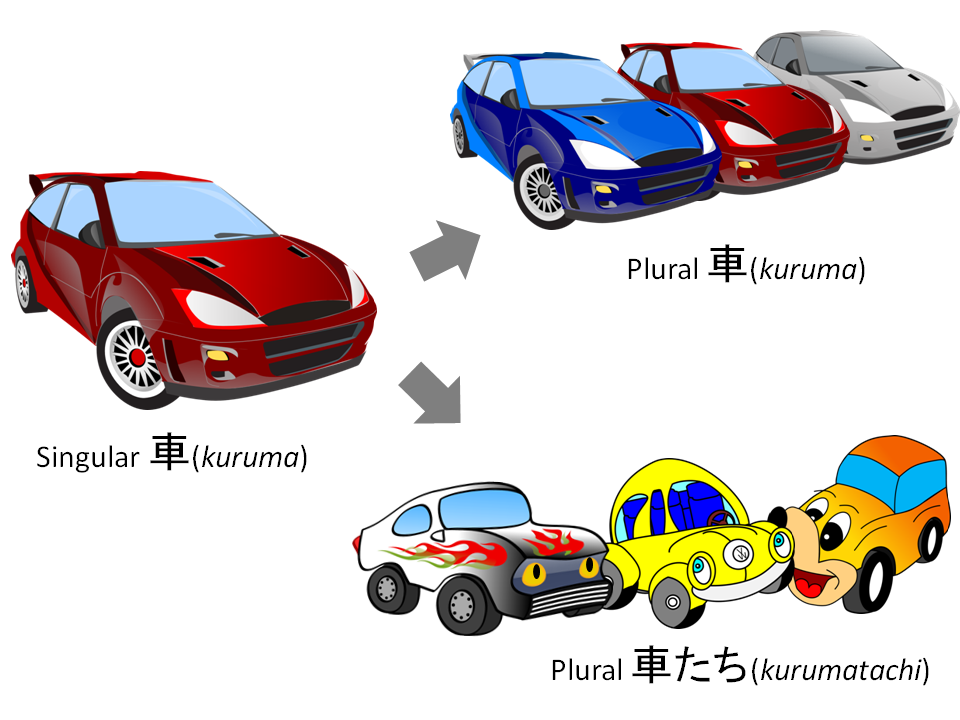

For example, Japanese has no plural form. There is no equivalent to adding –s to the end of a noun. When talking about people, a plural can be created by attaching たち (-tachi), such as 君たち (kimitachi, you+tachi = plural you) or 私たち (watashitachi, I/me+tachi = us). But when that’s applied to inanimate objects it sounds way too cute, like you’re anthropomorphizing. This might work for a children’s storybook but not for a business letter.

Compare this to English, German or Spanish that have a clear singular/plural distinction. Or some Slavic languages, where there is a plural form for two, and another for three and upwards. The linguist or the MT engine that’s translating from Japanese to other languages needs to gather from context whether, say, 車 (kuruma) means “car” or “cars.” Maybe if the phrase 玉突き事故 (tamatsukijiko, pileup) is somewhere in the source, you could assume it’s “cars,” while the presence of 走行距離 (soukoukyori, mileage, odometer reading) would suggest it’s a singular “car.” Currently the human linguist is far better at figuring out context than a machine.

The danger of gender

Many languages have gender-specific nouns in addition to neutral. For example, “actor” can mean someone in the profession of acting in general, or a male actor, while “actress” is a specific gender noun for a female actor. Likewise in Japanese, 俳優 (haiyuu, actor) can be a general term or a masculine noun, while 女優 (joyuu, actress) is specifically feminine. Same goes for 医師 (ishi, doctor) for general and masculine, and 女医 (joi, doctor) used specifically for female doctors. Since English has no term that differentiates the gender of doctors, you could say that Japanese is higher-resolution than English in this respect.

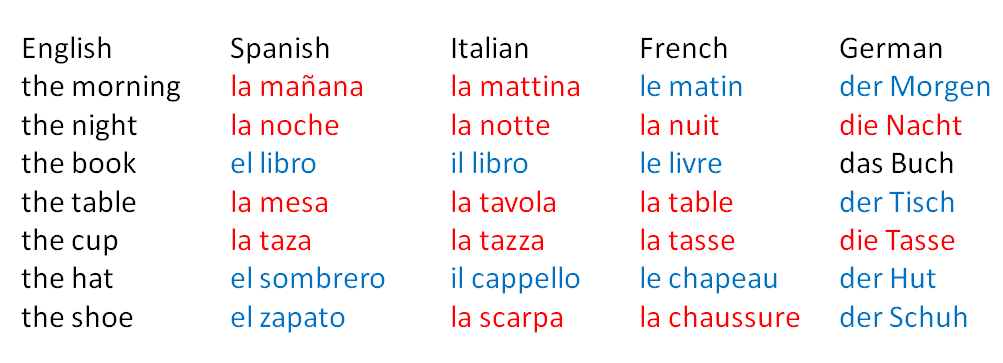

For some languages, gender spills over into inanimate objects. Romance languages like Spanish, French and Italian have masculine and feminine, while German and Russian have masculine, feminine and neutral. Who among us has not wondered at some point in life why a book has to be a boy, and a table needs to be a girl? It’s an extra complication when learning the language, but for the translator it’s a non-issue. The rules are clear cut so that even machine translation doesn’t get confused.

The tricky part is that the definite and indefinite articles a/the also have gender in these languages, so when a noun is replaced the article may also need to be changed accordingly. Many Asian languages including Japanese have no article, at all, so their linguists translating into other languages often find the proper use of articles quite challenging.

Bias ex machina

Google Translate ran into a problem a few years ago. Their revamped neural network-based Google Translate was discovered to skew translations toward masculine pronouns for some words, and feminine for others, so that, say, “doctor” was presumed to be male and “nurse” was presumed to be female. This was a reflection of the gender bias that found its way into their neural network-based system through the source materials used for training.

Google has since improved its system so that, according to the company, it “triggers gender-specific translations with an average precision of 97% (i.e., when we decide to show gender-specific translations we’re right 97% of the time).”

But is 3% inaccuracy allowable in a deliverable? Is “he” appearing even once in a text talking about a female doctor, acceptable? Especially in cases where there is a lot of resolution disparity between the source and target languages, it is advisable to at least involve a capable post-editor that can identify and correct such problems, because the improved fluency of machine translated outputs can wind up hiding the errors.

Other causes of resolution disparity

In terms of singular/plural distinction, Japanese is a lower-resolution language than English. It is also low-res in phonetics, comprised of only five vowel and 10 consonant sounds. As a result, when English terms get transliterated into Japanese, they lose resolution. Non-differentiation between L and R, as well as B and V, means words like “very,” “berry,” and “belly” all become ベリー (berii) in Japanese. So when ベリー pops up in the source text, the linguist must play context detective to figure out which berii it is.

But is Japanese always low-res? No, nothing’s that simple. Take, for instance, the Japanese word for “sister.” It can be 姉 (ane) or it can be 妹 (imouto). Because ane is an older sister, and imouto is a younger sister. Likewise, 兄 (ani) is older brother, and 弟 (otouto) is younger brother. In this sense, Japanese is higher-resolution than English. When an English source text says “I took my sister to school,” a linguist would likely translate “sister” as imouto, based on the situation being explained, while also keeping an eye out for any other hints throughout the source.

On the flip side, when translating 妹を学校まで送った (imouto wo gakkou made okutta) into English, the straightforward and safest solution would be “I took my younger sister to school.” But is that “younger” really necessary? Won’t a simple “took my sister to school” get the job done? That would depend on whether there’s an older sister in the picture also, making it necessary to draw a distinction, or if the relative age of the sister is somehow otherwise relevant.

Different languages pose different challenges. While 叔父 (oji) translates into “uncle” in English, how about other languages? In Bulgarian, there are five different words for “uncle”: Чичо (chícho) for a father’s brother, Калеко (kaléko) for a father’s sister’s husband, Вуйчо (vúycho) for a mother’s brother, Тетинчо (tetíncho) for a mother’s sister’s husband, and in Eastern Bulgaria, Свако (svako) for the husband of a mother’s or father’s sister. It’s up to the linguist to figure out if such distinctions can or should be applied based on the information supplied, or to seek clarification.

In general, the larger the resolution disparity between the source and target languages, the more challenging the translation task; especially when translating from low-res to high-res language. So if your client or boss approaches you assuming that English-to-Japanese is not much different from, say, English-to-Spanish, kindly let them know that this is not the case.

The dissimilarity means there’s more room for things to go wrong. Information crucial for a coherent target text might be missing in the source, requiring additional queries from translator to client. The SOV (Subject Object Verb) sentence structure of Japanese versus SVO (Subject Verb Object) for English can be a backbreaker (especially when interpreting). It’s also more likely that jargon or colloquialisms that exist in one language may be absent from the other.

And when translating from English to Japanese, remember that Japanese consumers are among the most demanding in the world when it comes to linguistic quality. Sub-par Japanese translations can and will hurt your brand image and negatively impact your business. Make sure your language solution is one that can bridge the gap of language resolution.

Douglass McGowan