When is English not English? When it’s used in Japanese. You see, the Japanese language includes a plethora of English loanwords that might be sliced, diced, and reinvented to suit Japanese sensibilities and needs.

Although there are a number of sources on the internet that talk about so-called Janglish or wasei-eigo, we would like to introduce a number of terms here categorized into five types.

Contents

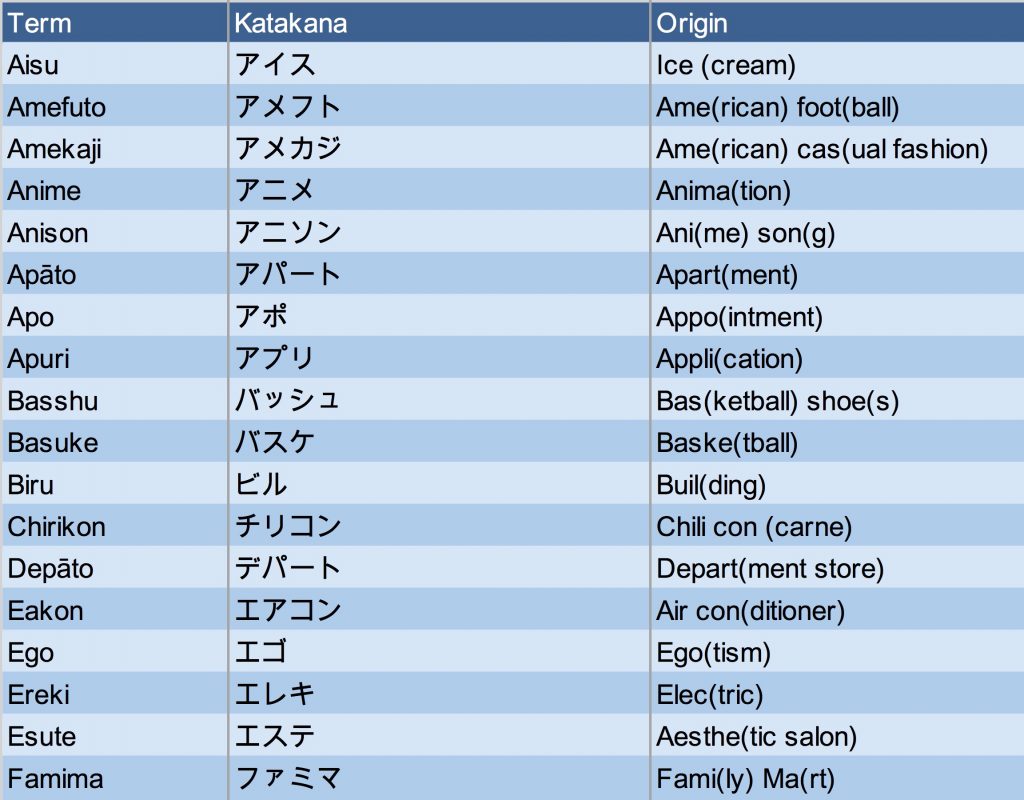

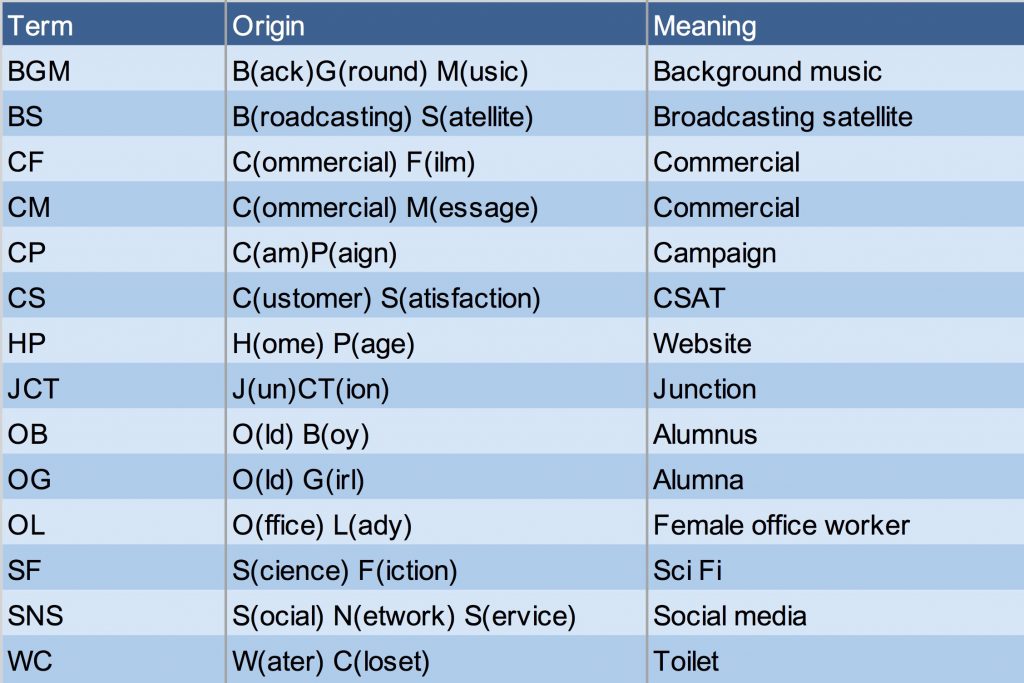

Type A: Truncated and Shortened Term

The most common driving force behind Janglish is the need to shorten loanwords. Let’s take the first item in this list, ice cream, for example. Read in English, it’s only two syllables. But when transliterated into Japanese it’s Aisukurīmu (pronounced eye-sue-koo-ree-moo, for five syllables). This is what you’ll find in the dictionary. But in real life, Japanese people will often shorten this to just Aisu.

Others like Apuri (for Application) are the short forms listed in the dictionary, much the way “App” has gained formal recognition in the English-speaking world.

Further down the list, you will notice Kentucky Fried Chicken being shortened to Kenta (ケンタ), and McDonald’s trimmed down to Makku (マック). Although these short forms are even used by the brands themselves, what’s interesting is that there are some regional differences in how those names are shortened. For instance, people in Osaka are likely to say Makudo (マクド) for McDonald’s, and Kenchiki (ケンチキ) for KFC.

* Swipe the image to view the rest of the list

The Japanese tendency to shorten loan words in such a way may stem from a centuries old tradition of shortening phrases written in kanji. Take the Japanese term for United Nations. The long form is 国際連合(kokusai rengō, United Nations), but this is regularly shortened to 国連 (kokuren). And it’s official. Whereas “United Nations” can be shortened to its initials, “UN” can also stand for “University of Nebraska,” “User Network” or “Uranium Nitride.” By contrast, 国連 is unique to the United Nations. In similar fashion, 東京大学 (Tōkyō Daigaku, Univ. of Tokyo) becomes 東大 (Tōdai), and 健康診断 (kenkō shindan, health check) becomes 健診 (kenshin) with essentially no loss of resolution. Reducing スケートボード(sukētobōdo, skateboard) to スケボー (sukebō) is the same basic idea.

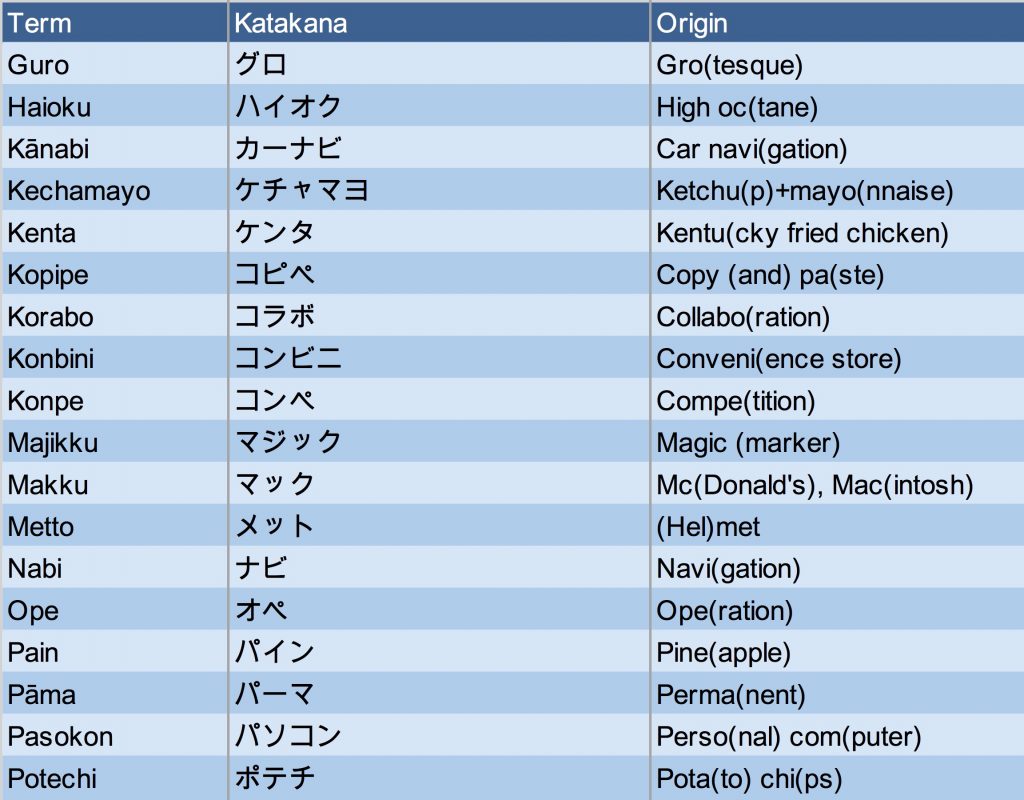

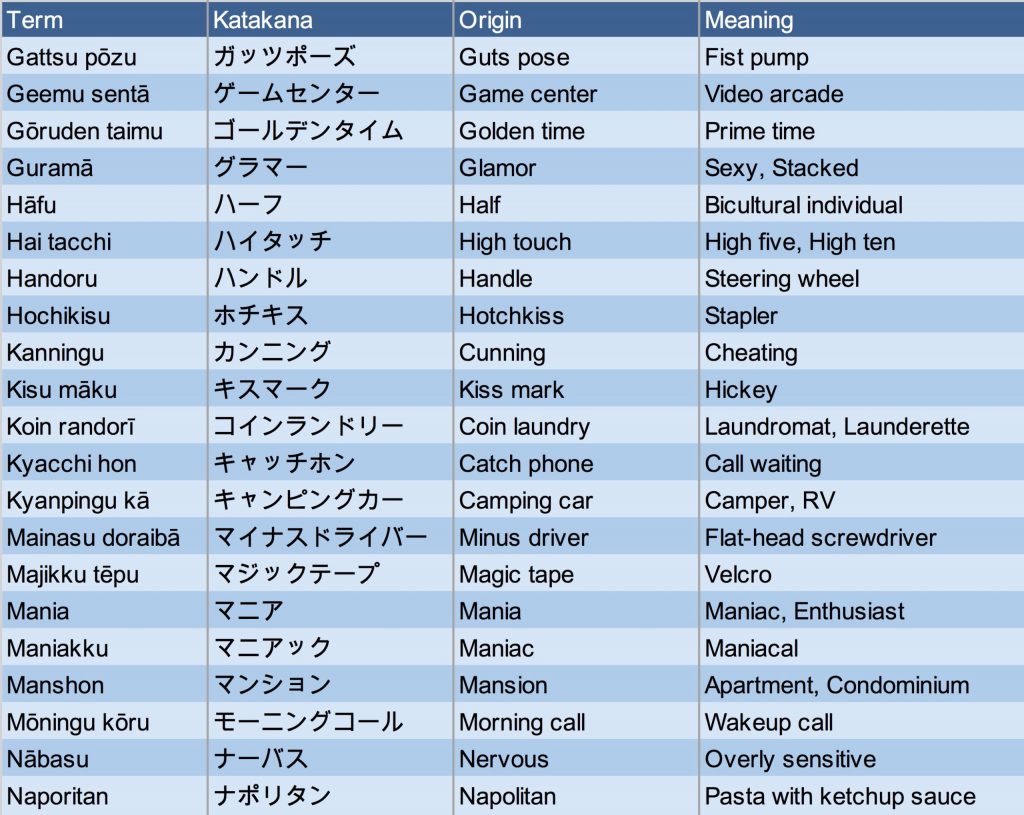

Type B: New Term or New Meaning

Some words, on their way from English to Japanese, gain new meanings. Other words are sort of made up in Japan. Perhaps using a bit of imagination you’ll be able to get from “Baby car” to “Stroller,” or from “Gasoline stand” to “Gas station.” But others are far more challenging. You’d be hard pressed to get from “Hotchkiss” to “Stapler,” from “Magic tape” to “Velcro,” or from “Pension” to “Cottage” on your own. Hotchkiss was the brand of stapler that stuck as the generic name, the way Kleenex and Xerox did in English. “Magic tape” is a colorful way of describing Velcro (which is a product name), and the etymology of “Pension” comes from pensioners who opened bed and breakfasts in their homes after retirement.

Some Japan-invented words actually make sense when you think about it. Take “Plus driver” and “Minus driver,” for instance. The “Driver” here is not driving a vehicle, but a screw. Knowing that, would you be able to tell which is a flat-head and which is a Phillips head screwdriver? Did you have your aha moment?

Finally, “Salaryman” is not a superhero that fights for a fixed wage, he’s just a white-collar office worker. The Clark Kent side of Superman.

* Swipe the image to view the rest of the list

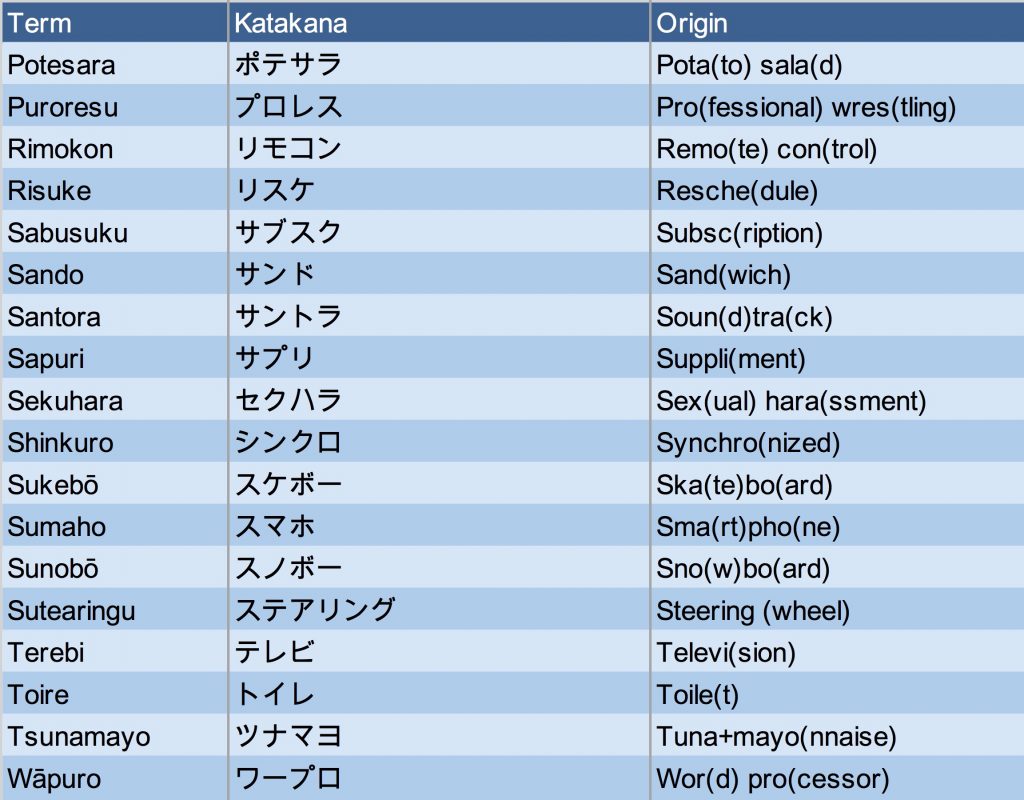

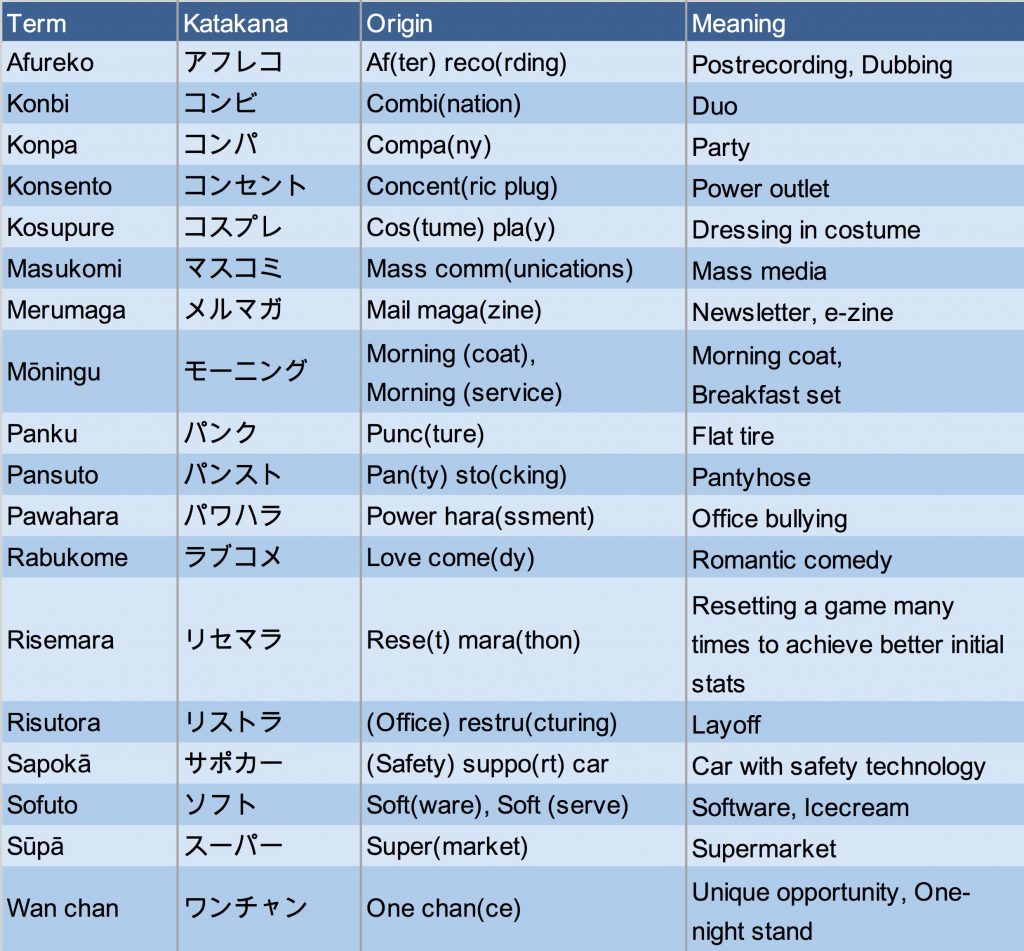

Type AB: Shortened with New Meaning

This group mixes the characteristics of the previous two. As a result, these Janglish phrases are among the most cryptic of them all. It also features a few phrases that can have multiple meanings, such as Morning (to mean either a Morning coat or a Breakfast set) and Soft (to mean either Software or Soft-serve ice cream). Although a bit tricky, the experienced translator should have no problem choosing the correct meaning based on context.

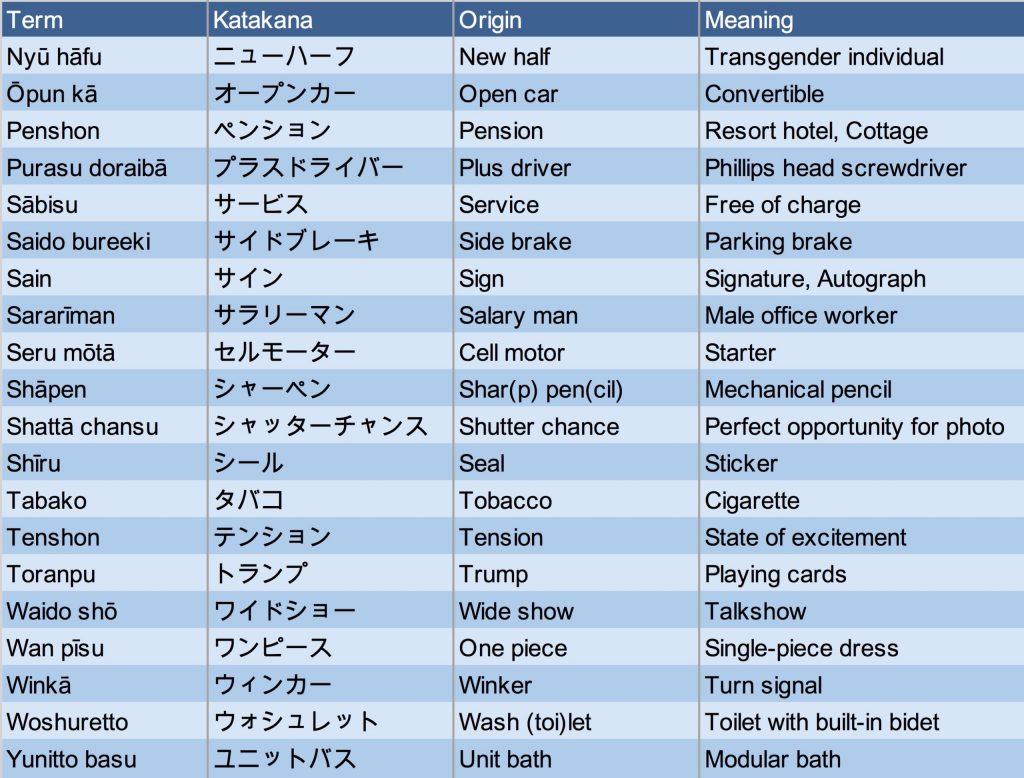

Type C: Initialisms and Pseudo-initialisms

Sometimes English phrases are initialized in different ways than you would expect in your home country. Some aren’t even initialisms or acronyms at all. Would you know what a Japanese person is praising if he or she says “Wow, nice BGM,” or who you might expect at the door when told “I invited OB and OG to the party”?

It should also be pointed out that “OL” is the female counterpart to a “Salaryman,” not LOL with a missing L.

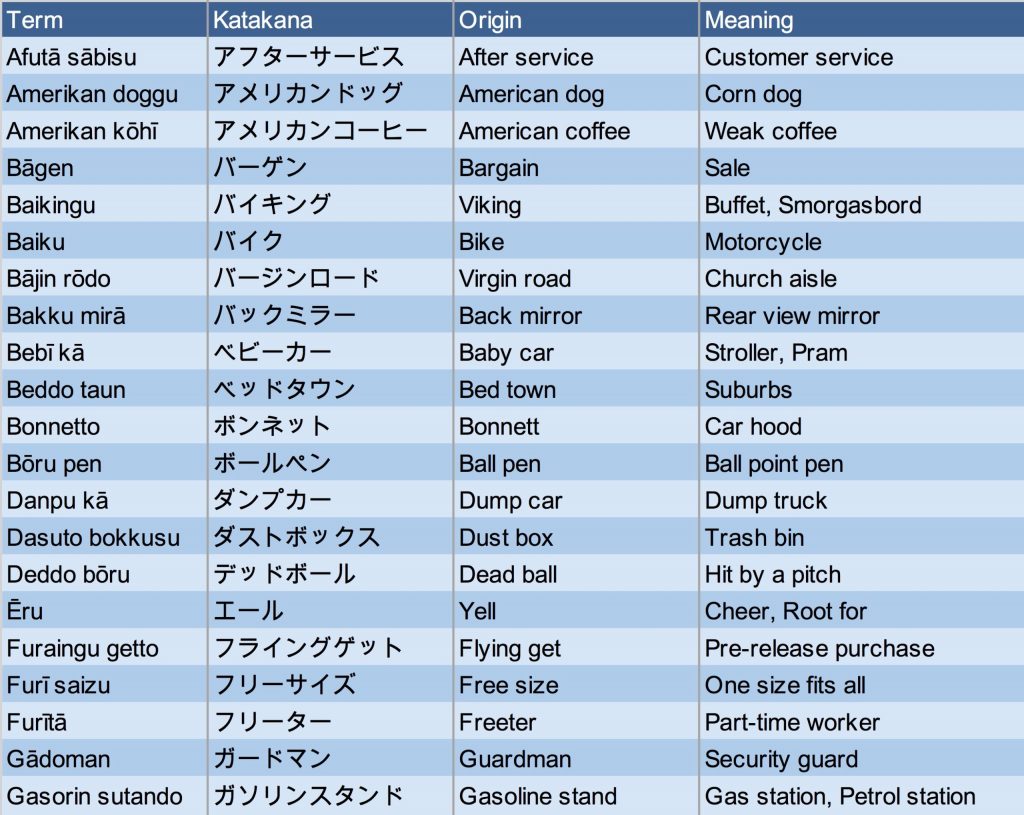

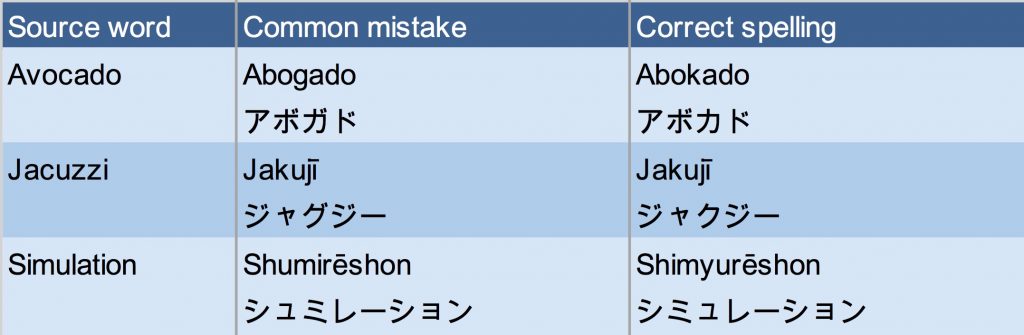

Type D: The Mistake

Then there are a few noteworthy common mistakes that Japanese people make.

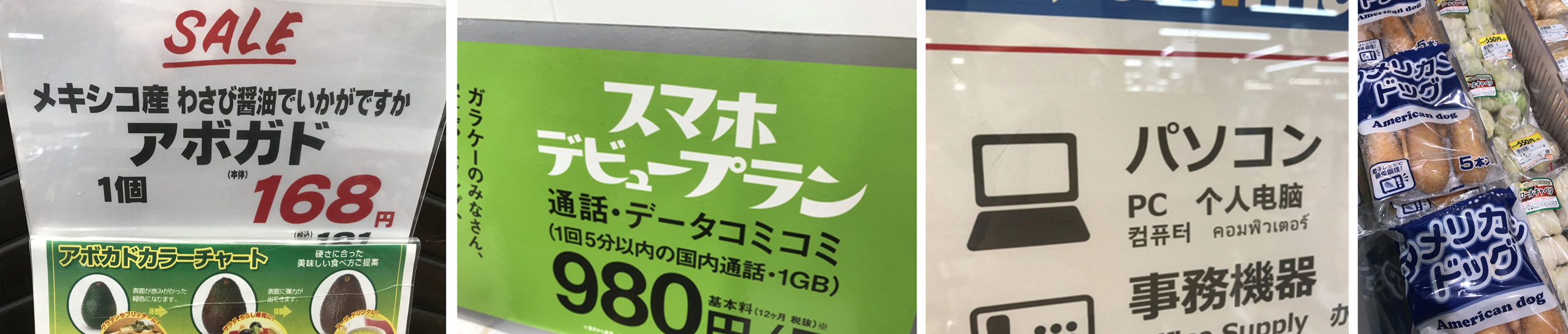

“Abogado” means “lawyer” in Spanish. But if you come across this in Japan it’s most likely an erroneous version of “Avocado.” Likewise, it’s not at all rare to find “Jacuzzi” winding up “Jaguzzi,” or “Simulation” being “Sumilation.” These mistakes are actually the result of Japanese speakers subconsciously “correcting” a difficult-to-pronounce sound into an easier one. To understand this phenomenon, it’s necessary to look at the katakana.

アボガド(abogado) vs. アボカド(abokado). In the first one, the dakuten dots on the カ character changes “ka” into a voiced “ga” sound, like the “bo” before it and “do” after it. This is a lot easier to pronounce than a-bo(voiced)-ka(not voiced)-do.

Likewise, with ジャグジー(jagujī) vs. ジャクジー(jakujī), having the voiced “j” “g” “j” sounds in a row is easier to pronounce than having the non-voiced “k” in the middle. What’s more, the Japanese word for a faucet is Jaguchi (蛇口), a false friend that the mind winds up associating with the hot tub’s name.

With シュミレーション(shumirēshon) vs. シミュレーション(shimyurēshon) it’s all about familiarity. Whereas the incorrect シュミ(shumi) rolls off the tongue with ease (because there’s a common word with the same pronunciation), the correct シミュ(shimyu) takes some tongue contortions to get out. It’s not a sound that occurs natively in Japanese. So like an obnoxious auto-correct when you’re tweeting, the mind auto-adjusts to the natural sound.

With all three of these examples, the mistake is so prevalent that if you are writing a Google ad, it would be a smart move to include the misspelled version in the keywords.

The Janglish listed in this blog post is not exhaustive. There are more, and they’re growing and evolving each day. Some are legit words you’ll find in a Japanese dictionary, while others are more slangy. When translating, these Janglish terms post a double threat. First, the translator or MT engine obviously needs to know them. But the real threat is more hidden. Translating Manshon as “mansion,” Hāfu as “half” or Panku as “punk” might be embarrassingly wrong because of the unique meanings given to them in Japanese. Understanding these potential pitfalls is key to effective Japanese-to-English or English-to-Japanese localization.

Douglass McGowan