People learning Japanese are inevitably exposed to dajare (駄洒落), or Japanese puns, along the way. Like anything in life, some people like them and some people don’t. But then again, puns and dajare are an acquired taste, so isn’t that natural? Well, there may be a bit more to it than just ‘learning to like it.’

We did some digging online to discover what factors may be involved in whether you might develop that taste for dajare, and combined with personal experience, we narrowed the variables down to these five key factors: (1) Your age, (2) Your gender, (3) Your level of Japanese vocabulary, (4) Your relationship with the teller of the dajare, and the (5) Type of humor you prefer, all of which are interlinked. Interestingly, some of these factors may suggest that foreign learners of Japanese could have a built-in advantage, but more about this later.

Contents

What’s dajare?

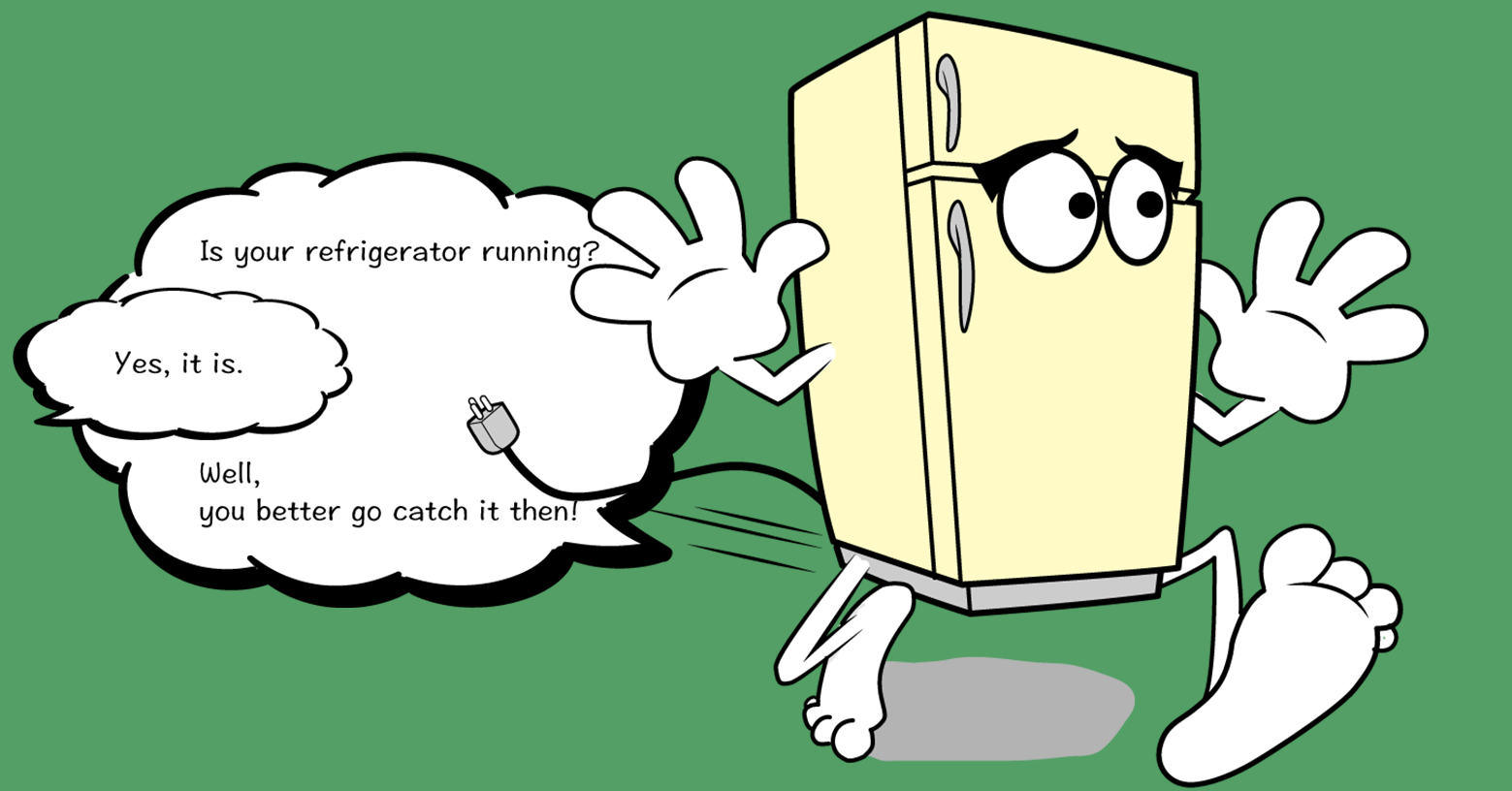

Before we dive, let’s briefly take a look at what we’re talking about. Dajare is word-play using a pair of words that sound the same or similar to each other, or to put it simply, a pun. A variant of dajare is the oyajigyagu (which means literally “dad joke”) that is frequently the cause of much eye-rolling on the part of spouses and children universally.

People who are really good at dajare might even want to do it professionally. Dajare are a key element in the punch lines of traditional rakugo (落語) storytelling as well as nazokake (なぞかけ) riddles which take dajare to an advanced level.

Some foreigners might actually become so proficient at dajare that they become like Gregory Robic, who’s known in Japan as Katsura Sunshine (桂三輝). This is not just some Japanophile who tells jokes while cosplaying in a kimono, he’s the real deal, a professional rakugoka and bona fide member of the House of Katsura.

Whether you like dajare depends on who you are

Puns are one of the building blocks of ‘dad jokes,’ as you well know. As in “what do you call a fish wearing a bowtie? So-fish-ticated.” And like those dad jokes that seem so hilarious to some middle-aged men near you, Japan has its own version called oyaji gyagu. But whereas dad jokes are often associated with fathers trying desperately to narrow the distance between themselves and their children, oyaji gyagu are also used, and even abused, in the Japanese workplace by bosses toward their subordinates. Coincidentally, oyaji means both ‘dad’ and ‘old man’ so we know which oyaji is attributed to workplace bosses.

So, why is it that middle-aged men go for puns and dajare the way they do? Let’s see how the five key factors mentioned at the beginning weigh in. First, your age. With age, there is an increase in vocabulary that makes it easier to pull out words from memory to use in puns. This is pretty much what you’d expect, right? But another, less comfortable truth, is that at around age 50 the human brain begins to deteriorate in ways that eventually lead to decreased self-control, and the pun teller becomes less and less likely to think twice before blurting it out. Taken to the extreme, some elderly folks revert to a child-like state, where inhibitions give way to compulsive behavior. But don’t be alarmed. Not being able to keep a pun to yourself does not necessarily mean you’re in need of medical attention.

Next, your gender. International studies have found that “Although both sexes say they want a sense of humor … women interpreted this as ‘someone who makes me laugh,’ and men wanted ‘someone who laughs at my jokes.’” So both males and females believe a sense of humor is an important or attractive characteristic when seeking a relationship, but there’s a difference as to how it’s applied, which then leads us to another factor: your relationship to the joke teller. Whether you’re a man or woman, if you’re the person telling the joke you’ll probably think it’s funny. But if you’re on the receiving end of the joke, your relationship with the joke teller becomes critical. The same joke told by someone you like or love, and someone you dislike or have zero feelings for, will land differently.

Some Japanese articles online claim that the male and female brains actually react differently upon hearing a word. According to them, male brains tend to associate the word with other words that sound the same or similar (the essence of a pun), while female brains tend to link the word with memories from the past in a nostalgic way. If this is indeed true, it would further explain why men embrace dajare more readily. Meanwhile, in their paper entitled “Japanese Puns Are Not Necessarily Jokes,” a research team at Hokkaido University asked participants whether they considered dajare (puns) to be jokes (implying they are funny), and while 46% of male respondents thought dajare were a type of joke, only 35% of females thought the same. Pity be on those 11% of men who tell their wives or girlfriends a dajare expecting, yet not receiving, a smile in return.

Why some Japanese learners find dajare so appealing

Contributing to the relative ease of creating puns in Japanese is the limited number of sounds in the spoken language. Fifteen consonant sounds combined with only five vowel sounds in specific combinations. In the written language, confusion can be avoided depending on the characters used, especially when heterographic kanji characters come into play. For example, the word shibō has lots of potential as a dajare since it could mean ‘ambition,’ ‘fat,’ or ‘death.’ When you consider the kanji characters, the difference becomes clear since 志望 (shibō: ambition), 脂肪 (shibō: fat) and 死亡 (shibō: death) are clearly not the same. Puns work with the aural ambiguity presented by the words, combined with the different meanings that deliver the ah-ha effect in the punch line.

When you’re a foreigner learning the Japanese language, you start by learning the sounds. So as your Japanese vocabulary grows it’s stored in your brain phonetically (perhaps in alphabetical romaji form) without ‘interference’ from the more complex kanji characters. Whether the foreigner can truly master the art is another matter, but this relatively simple mechanism of matching sounds does provide an easy onramp to get started. Perhaps Katsura Sunshine began his relationship with the Japanese language this way, as have so many other foreigners who are quite adept at the craft.

Try Googling “ダジャレ 外国人” (dajare +foreigner) in Japanese, and the first result displayed will be the Wikipedia entry for a person named Dave Spector. Dave is a TV producer and personality based in Japan, where he’s also famous for the endless stream of dajare whenever he’s on TV and in his Twitter feed. Sometimes quantity trumps quality.

When Scott Oelkers became CEO of Domino’s Pizza Japan, he made headlines not only by personally appearing in their TV commercials but also by launching a special campaign site called “DAJARE-A-DAY ダジャレやで~” on which he posted, you guessed it, dajare.

On the Japanese comedy scene, folks like American Patrick Harlan from the duo Pakkun Makkun, and Australian comedian Chad Mullane, all contribute to bridging the distance between Japan and the Western world with dajare and other things that make people laugh.

If you don’t find dajare like futon ga futtonda (the futon flew away) appealing at all, the reasons for that may be as complex as the reasons why someone else would like it. Your age, gender, level of Japanese vocab, relationship with the teller of the dajare, and the type of humor you prefer (hint: if you don’t like puns you won’t like dajare) are all contributing factors. But if you’re learning Japanese, please don’t rule them out as an effective way to increase your word stack.

In closing, let’s take a moment to appreciate this gem of a nazokake riddle: What’s the similarity between the morning newspaper (chōkan: 朝刊) and a Buddhist monk (bōsan: 坊さん)? Answer: Dochiramo kesa kite kyō yomu. Explained: Dochiramo is the common part to all nazokake and it means “they both,” but the key is what comes after that. Kesa kite kyō yomu can either be 今朝来て今日読む (comes in the morning and is read today), or 袈裟着て経読む (wears a monk’s stole and chants a sutra). If you’re able to pull off a nazokake of this level, you might want to consider going professional yourself.

Douglass McGowan

Subscribe