Japanese people love baseball. A steady stream of high-level talent that have arrived on American shores, spearheaded by Hideo Nomo, Ichiro and “Godzilla” Hideki Matsui, and more recently in the form of “Shotime” Shohei Ohtani, show us the depth of Japan’s love affair with the sport. Another fact about Japan is that they can be rather strict about rules. So it was interesting to see these two characteristics come to a head late last year when it was discovered there was a problem with Japan’s newest baseball park, Es Con Field Hokkaido, the new home ground for Shohei Ohtani’s old team.

Contents

Too close for comfort… and for the rulebook

Es Con Field Hokkaido was designed with the concept of providing fans with a more immersive experience, like many Major League Baseball teams in the U.S. provide, by bringing them closer to the action. The Nippon Ham Fighters even hired the American firm HKS to design their new ballpark precisely because of their expertise in this area, much impressed by their work on Globe Life Field where the Texas Rangers play. But just days before the scheduled grand opening ceremony of Es Con Field Hokkaido, it came to light that the distance between home base and the backstop was too short, according to the rulebook. The Japanese rulebook, that is.

Japanese baseball fans were excited about how close the backstop was to home base with only 15 meters (49′) separating them, bringing spectators closer to the action. Compare this to the average Japanese pro baseball stadium with 19 meters (62′) separation, and even more notably the Fighters’ previous stadium which had about 25 meters (82′) of real estate in between. The new design was heralded as ushering in a new era of baseball in Japan, but alas, it was a violation of the rules which state:

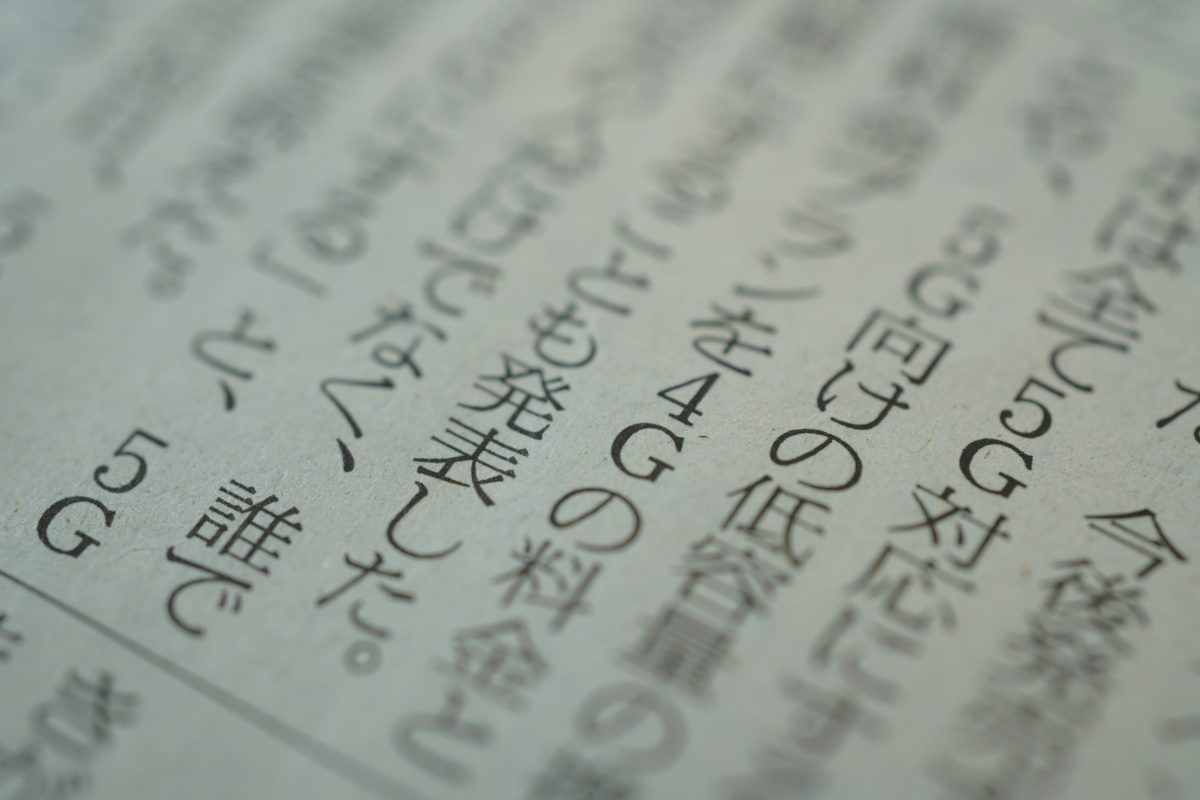

本塁からバックストップまでの距離、塁線からファウルグラウンドにあるフェンス、スタンドまたはプレイの妨げになる施設までの距離は、60㌳(18.288㍍)以上を必要とする。

Translation: The distance from home base to the backstop, and from the base lines to the nearest fence, stand or other obstruction on foul territory shall be 60 feet (18.288 meters) or more.

The rules are pretty clear about the distance requirement. So how on earth did Es Con Field Hokkaido end up with just 15 meters between home base and backstop? Let’s take a closer look.

To back translate or not to back translate

When there’s an original document in English, and a translated document in Japanese, and you want to see what that Japanese document says in English, what do you do? The logical step that most people would take is to refer back to the original English document. Back-translating from Japanese to English would seem like not only a waste of time, but also increasing the risk of introducing errors.

So, as HKS is an American company, it’s not hard to imagine the Japanese client asked HKS to refer to the “original” English rules for guidance. Nothing could be surer. What could possibly go wrong?

In this particular case, however, it’s ironic that a back translation may have helped avoid a lot of headaches for a lot of people.

Time for some forensics

Now that we assume that HKS was working based on the original English Official Baseball Rules instead of the Japanese version, let’s look at what it actually says. And there it is, in section 2.01 Layout of the Field, paragraph 4.

It is recommended that the distance from home base to the backstop, and from the base lines to the nearest fence, stand or other obstruction on foul territory shall be 60 feet or more.

So, in the English version the distance “requirement” isn’t a requirement at all, it’s a recommendation. A recommendation that HKS didn’t follow when they designed Globe Life Field in Texas with only 42 feet (just under 13 meters) separating home plate from the backstop.

Comparing the English and Japanese versions of the same document, we can see that the Ex Con Field Hokkaido debacle was an accident waiting to happen. Because the ballpark that broke the rules (i.e. only 15 meters between home plate and backstop) was exactly what the client asked for (i.e. a ballpark like the Texas Rangers’ Globe Life Field). The problem was baked in.

So how did this disparity between English and Japanese happen in the first place? NPB (Nippon Professional Baseball Organization), Japanese baseball’s governing body, has not shed any light on the “why” part of this mystery, so we can only guess.

We checked with older versions of the Official Baseball Rules to see whether the “It is recommended that” part of the sentence was a recent addition that wasn’t reflected in the Japanese version due to timing issues, and quickly found that the same exact wording had existed back in 2010 and most likely goes back even further. So it wasn’t an inadvertent curve ball added to the English that the Japanese missed.

Another possibility is that there was some confusion on the part of the translator due to the seemingly contradictory nature of the sentence that includes both “shall be” and “it is recommended.” You see, in legalese, “shall” holds the same weight as “must” in that it is an imperative command that imposes requirements, while “it is recommended” dilutes the imperativeness by making the requirement optional. Something like being told “You must do that if you want to.” And perhaps some folks decided to err on the side of the stricter interpretation.

Some in Japanese media have criticized the translation on the grounds that “It is recommended” was erroneously translated into 必要とする (hitsuyō to suru: required) when it should have been 推奨される (suishō sareru: recommended), and conversely that for the必要とするtranslation to make sense, the original English would have had to say “It is required.” This is only half true, however, because the essence of “required” already exists in the term “shall.”

All’s well that ends well?

NPB had an “illegal” ballpark on their hands and the 2023 season was approaching. Other teams in the league were crying foul because the narrower foul ground of the new ballpark would reduce the chances of a foul fly hit to the rear being caught, giving the Fighters an unfair advantage (not per game but over the season). But redoing the design to meet regulations would jeopardize the upcoming baseball season for the entire league.

So, in a move that has been called “a compromise solution that nobody is happy about” in some Japanese media, NPB decided to allow games at Es Con Field Hokkaido under the condition that Nippon Ham carry out renovations the following offseason to bring the ballpark into line with the rules, much to the disappointment of baseball fans. To date, there is no discussion as to changing the Japanese rules to bring them into line with the English rules.

Any problem, any epic fail, has a takeaway we can learn from. In the case of Es Con Field Hokkaido, we see the importance of making sure that all parties involved are playing by the same rules before entering the game. Don’t assume, just confirm. Here the assumption was that the English and Japanese Official Baseball Rules were equal, but they weren’t. And all English aside, why weren’t Japanese people checking the Japanese rules against the Japanese ballpark to make sure things were legit? Perhaps the assumption that things couldn’t possibly go wrong? As a result, officials had to scramble at the last minute for a compromise that nobody was happy about (but everybody could live with). A major catastrophe was avoided, but we nearly witnessed Japan’s newest ballpark strike out even before the first pitch was thrown.

Douglass McGowan