(*Linked or embedded content may have been removed or be unavailable.)

The original Olympic motto consists of three Latin words: Citius, Altius, Fortius (for Faster, Higher, Stronger)*. Latin may make for an inspiring motto, but it’s not the ideal language for communication at sporting events. Now that we’ve experienced the excitement and drama of Paris 2024, let’s take a look back at how language and translation are intertwined with this spectacular sporting and cultural event that comes around only once every four years (well, once every two years when you factor in both the summer and winter games).

Contents

Official languages of the Olympic and Paralympic Games

The Olympics have three official languages: French, English, and the language of the host country. In the case of Paris 2024, French was also the language of the host country so French and English were the only official languages.

The reasoning behind why French and English are permanent official languages is both pragmatic and historic. As you may know, the Olympics has its roots in the ancient Olympic games held at the Panhellenic sanctuary of Olympia in Greece (8th century BCE to 4th century CE). But the modern Olympics came about due to the efforts of Baron Pierre de Coubertin who founded the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1894, leading to the first modern Games in Athens two years later in 1896. And the reality of the 19th century was that Great Britain and France were the two preeminent global powers back them, giving their two languages unprecedented global reach. Also, French was historically considered the language of international diplomacy whereas English was the lingua franca of international business. Added to that, Monsieur Coubertin was a Frenchman, so it’s not a leap to assume that selecting French as an official language was not at least in part a hats-off to the Olympic movement’s founder.

Language-wise, the Paralympics, which began in 1988, follow the same official language scheme as the Olympics. But as the sporting events involve athletes with various disabilities, linguistic accommodation becomes even more challenging, as we will go into further detail later.

Translation technology for the win?

Advancements in translation technology, such as machine translation and speech recognition, play a crucial role in overcoming language barriers at the Olympics. And since Paris 2025 featured athletes gathered from over 200 countries around the world, such technologies obviously came in handy.

Have you ever noticed an athlete, after a match, walk over to a camera crew and put on headsets? That’s one example. During post-event interviews, athletes and coaches often wear headsets that allow for real-time interpretation of their responses into multiple languages, ensuring that viewers worldwide can understand the content, regardless of their native language.

People today are very dependent on their smartphones for a variety of reasons, and athletes are no exception. Athletes use translation apps on their smartphones to communicate with people from different linguistic backgrounds, whether it’s mingling at the Olympic Village, visiting local sites or ordering food. And using a smartphone app is a lot less unwieldy and costly than having an interpreter accompany each individual athlete. But of course, Olympic Villages often provide on-site translation and interpretation services to help athletes and officials communicate with each other when needed.

The Paris 2024 Olympics were broadcast by a record number of broadcasters from around the world. While an exact number is not publicly available, it’s estimated that hundreds of broadcasters in various countries and territories acquired the rights to televise the Games. These Olympic broadcasts often include subtitles or captions in multiple languages, making the events accessible to viewers with hearing impairments or who do not speak the original language.

Sports is often its own language

When you use sports terminology, it might not be English even though you may think it is. Granted that since many terms are indeed English since many sports originated in the English-speaking world, you will find other languages hidden there. For example, did you know that “Rally” comes from the French word “rallier,” meaning “to reassemble”? Or that “Foul” comes from the French “foule,” meaning “crowd”? Or that “Court” comes from French “cour” for “yard”? Well, many of these date back to the complex origins of English, so let’s move on to more recent entries from other languages.

It wasn’t until the 1964 Tokyo Olympics that Judo terms like “Ippon” (a decisive throw or submission), “Waza-ari” (a near-fall or effective control), “Hajime” (command to start) and “Mate” (command to stop) entered the sporting lexicon. Likewise, the 1988 Seoul Olympics saw Taekwondo terms like “Gam-jeong” (awarding a point based on the force and accuracy of a technique, “Kyo-sim” (stopping the match due to a violation or injury) and “Hansok” (penalty resulting in a point deduction or disqualification) entering the mainstream sports world.

As Olympic sports continue to change and diversify, we may be seeing even more interesting new terminologies in the future if and when other Asian sports such as Sepak Takraw and Kabaddi, Brazilian Capoeira, or the Basque-origin Jai Alai (which was once popular worldwide) ever enter the Olympic lineup.

Path forward for the hearing impaired

To ensure inclusivity for athletes and spectators with hearing impairments, sign language interpreters are often present at Olympic events. And this is actually much more complicated than you might expect, as it requires a working knowledge of at least two spoken languages as well as two sign languages (making it essentially four languages). And unlike the misconception of sign language being borderless, as it indeed was among native American tribes who spoke different languages but communicated through common hand signs during the pre-colonial era, in the modern world it is estimated that there are over 300 different sign languages used around the globe.

Each sign language has its own unique grammar, vocabulary, and cultural context. Even within the English-speaking world, American Sign Language (ASL) is different from Australia’s Auslan sign language, which is different from the British Sign Language (BSL) used in the UK.

The prevalence of machine translation and proliferation of smartphones will undoubtedly mean more reliance on translations being quickly displayed on screens instead of sign language interpreters going forward.

Lost in translation on the world stage

Despite best efforts and good intentions, language-related mishaps can occur at the Olympics, just like anywhere else. These can range from mistranslations in official documents to misunderstandings during interviews and embarrassing slogans. Most don’t make headline news, but here are just a couple examples to give you a taste.

During a match at the Tokyo 2020 games, an athlete amused Korean-speaking onlookers when they showed up at the finals wearing a black belt that said “Gicha hadeu, Kkum keun,” a Korean mistranslation of the slogan “Train Hard, Dream Big.” In addition to having jumbled syntax, “gicha” (기차) is a noun meaning “railway train” and not the verb meaning “to train to learn a skill.”

Norway’s Olympic team chefs at the 2018 Pyeongchang winter games used Google Translate to order their groceries at a local supermarket, including 1,500 eggs. But as it went through the translation app, the order morphed into 15,000 eggs by the time it arrived (MT does have trouble with numbers sometimes). The story did end well, however, as the grocery store was gracious enough to take the excess back, relieved to learn that the Norwegians were not the egg-overeaters they had feared.

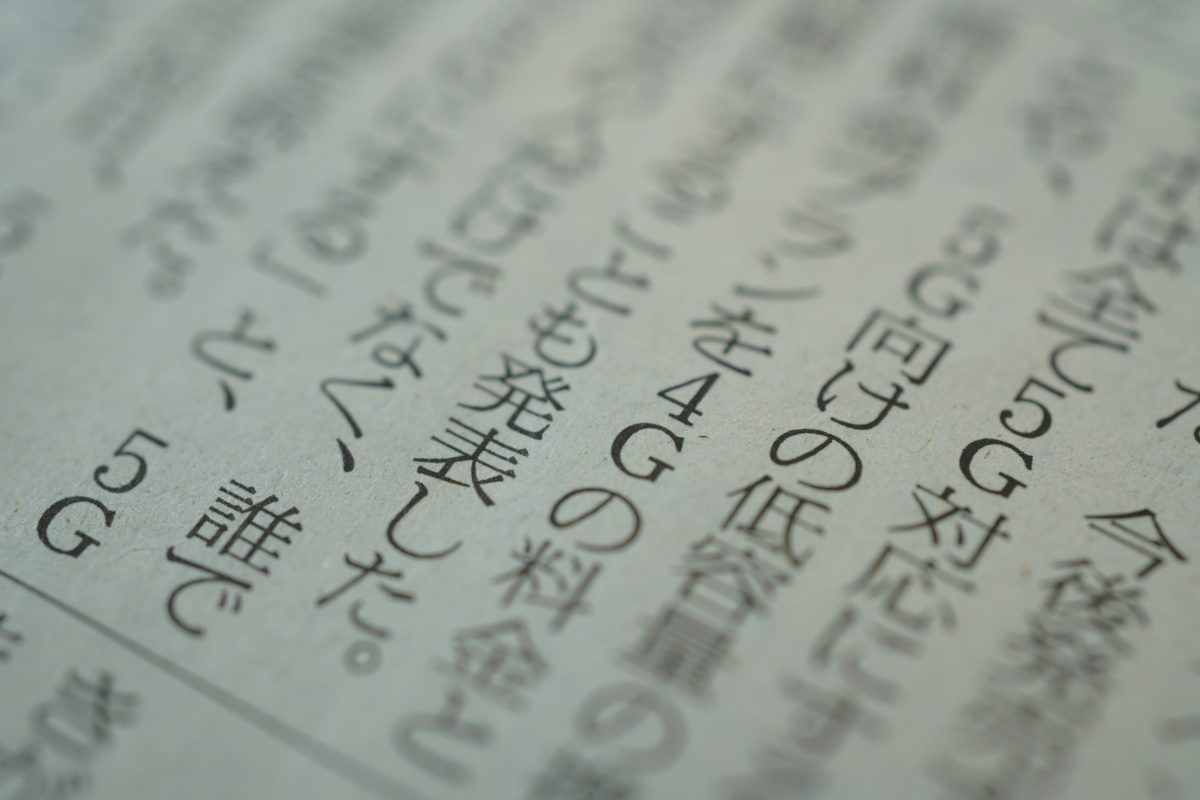

On a slightly more serious matter, during discussions leading up to Tokyo 2020 (which was held in 2021 due to the pandemic), IOC Chairman Thomas Bach was quoted as saying “We have to make some sacrifices to make this possible.” The Japanese media then picked this up using the translation 「五輪のために誰もがいくらかの犠牲を払わないといけない」(We all have to make some sacrifices for the Olympics.), to which a Japanese opposition party retorted 「命を犠牲にしてまで五輪に協力する義務は誰にもない」(No one is obligated to cooperate with the Olympics at the cost of their lives). This is a case of a translation going sideways due to lack of sufficient context, a tense political environment, and the anxiety of dealing with an uncertain future.

As the 2024 Paris Olympics and Paralympics teach us, we could all use a little more Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) in our lives. And for those wondering why on earth then, if the Olympics originated in Greece, is the official motto in Latin instead of Greek, well, let’s just say — C’est la vie!

* The Olympic motto was updated in July 2021 to include a message meant to inspire unity: Citius, Altius, Fortius – Communiter (Faster, Higher, Stronger – Together)

Douglass McGowan