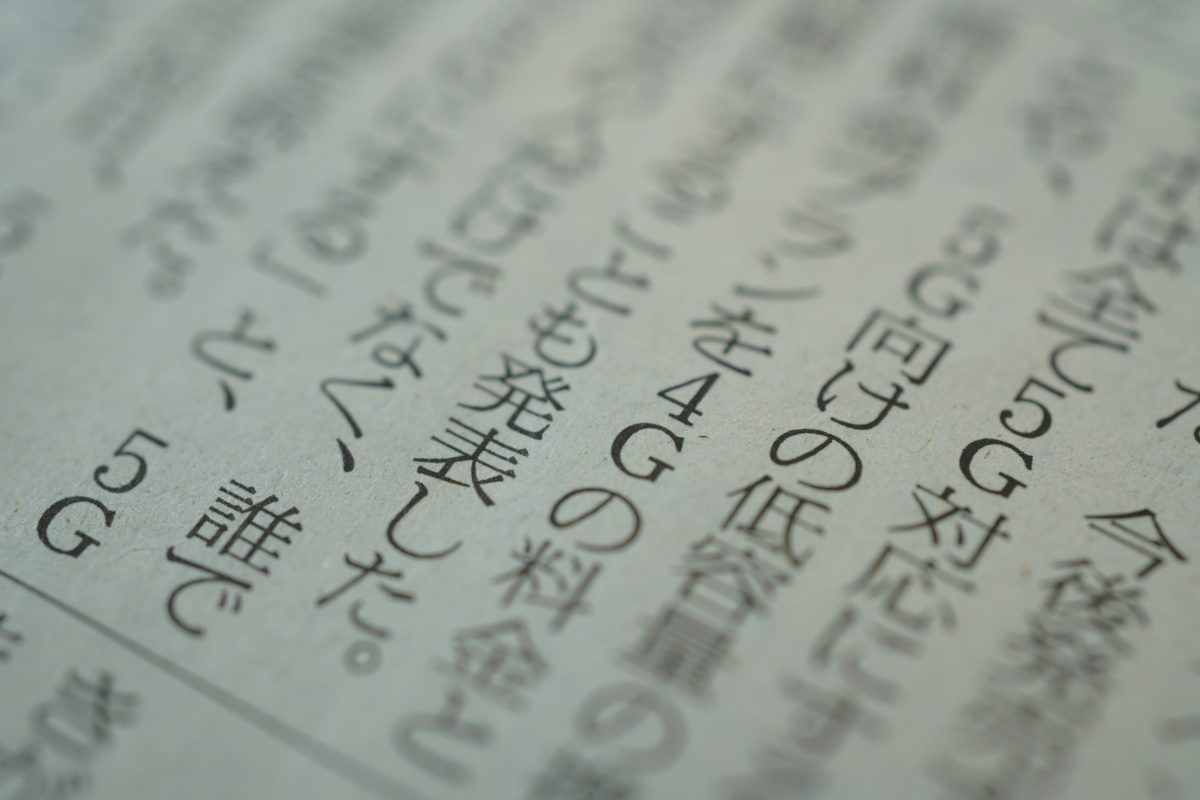

Did you know that there are some Japanese words that have found their way into English, largely unnoticed like stealthy little ninja? No, we’re not talking about sushi, tofu or wasabi. Those are obviously Japanese based on context; you’ll find them at a Japanese restaurant or when Googling Japanese food. There’s a different group of words that many folks use in their daily lives as plain ol’ English without knowing they actually immigrated from Japan long ago.

Tycoon

English speakers regularly use this word interchangeably with “magnate” or “mogul” to refer to a person who has succeeded in business or industry and has become very rich and powerful. As such, “tycoon” has made its way into mainstream culture through journalism, music, simulation games, and even a John Wayne movie.

Today translators coming across “tycoon” would localize it into Japanese as 富豪 (fugō), 長者 (chōja) or maybe 大物 (ōmono). Huh? They don’t sound like “tycoon” at all, right? That’s because although English tycoon comes from Japanese 大君 (taikun), back in Japan that word refers specifically to a feudal lord or shogun, not a successful businessperson. Interestingly, this same character combination can be read 大君 (ōkimi), in which case it refers to the emperor or the crown prince/princess, reminding us how important context is in Japanese.

Skosh

You may be old enough to remember Levi’s blue jeans “With a Skosh More Room” that were on the market in the late 70s to early 80s for post-adolescent jeans wearers. Even if you’re not, Googling the phrase will lead you to plenty of vintage jeans featuring that tag. As you may have guessed, the term “skosh” means “a little bit” or “a smidgen,” but contrary to what some may think, it was not a word made up by Levi’s for marketing purposes, but derived from the Japanese 少し (sukoshi) meaning “a little, a bit, or slightly.”

According to The Straight Dope, a popular question-and-answer column published in The Chicago Reader from 1973 to 2018, “United Nations troops first picked it up during the Korean War, presumably while on R and R in Japan, and it’s been part of military slang ever since,” as a unit of measure applied to “any dimension smaller than a centimeter and larger than an angstrom.” People continue to use it today, albeit maybe not quite so often.

Honcho

Although many wrongfully assume that “honcho” has Spanish origins based on the way it sounds, the word originates from the Japanese term 班長 (hanchō), meaning “team leader” or “squad leader,” and is another one of those words that soldiers brought home with them from the field. The English-speaking world developed the term “head honcho” to mean the “person in charge,” and is synonymous with “boss,” “chief,” “foreman,” and in British English, “gaffer.”

Today “head honcho” can be found in brand names for men’s hair and skin care products, men’s clothing, as well as in rap and punk rock tune titles and artist names. Digging deeper we find that “head honcho” also carries the street connotation of “a person with advantages over the rest, though he or she may not be any more qualified than the others” according to the Urban Dictionary. Back in Japan, hanchō is rarely heard outside of the school system and TV crime dramas (referring to a detective and not a gangster).

Kudzu

Kudzu (a.k.a. Kudzoo, a.k.a. The Vine that Ate the South) came to the US in 1876 as part of the International Exhibition held in Philadelphia, PA, in both name and form. Kudzu, from Japanese 葛 (kuzu), was introduced as a soil erosion-control plant species, and actively cultivated after the 1930s Dust Bowl to protect and revitalize the land, as well as feed grazing livestock, which all seemed like a good idea at the time. Fast-forward a few decades and kudzu, having been a skosh too successful in its growth, finds itself designated as a noxious weed.

Some seek “revenge” against this plant by consuming it – as in eating and drinking it. Actually this idea is not as farfetched as you might think, because in kudzu’s native Asia, there is a centuries-long tradition of using the plant not only to weave baskets and make paper, but also to eat.

Bokeh

If you’re into photography, you’re likely to have come across this term already. Bokeh comes from the Japanese word ボケor 暈け (boke) which means “blur.” In photography, bokeh refers to the out-of-focus background or foreground of an image, and is also used to mean what Japanese people call ボケ味 (boke aji) for “quality of blur” or ボケ足 (boke ashi) for “depth of blur.” The English spelling “bokeh” was popularized in 1997 in Photo Techniques magazine, in a move meant to encourage correct pronunciation (it rhymes with croquet, not with poke) although a lot of people wind up mispronouncing it anyway.

Tsunami

Today “tsunami” is a bona fide English word that appears in both American and UK English dictionaries, but it originates from the Japanese term 津波 (tsunami). In both Japanese and in English, the word refers to “an extremely large wave caused by a violent movement of the earth under the sea.” Although “tsunami” first appeared in National Geographic Magazine way back in 1896, the English-speaking world commonly referred to this phenomenon as a “tidal wave” until 2004 when the killer wave struck Indonesia. The scientific community welcomed the new word as a way to differentiate the seismic wave from a true tidal wave that is caused by the gravitational force of the sun and moon, not a quake.

Many Anglophones find tsunami hard to pronounce correctly, as the “ts” combination is not natively found at the beginning of English words. A trick you might use to nail the “ts” sound is think “boo tsunami!” The “ts” should roll off the tongue as easily as saying “boots.” Piece of cake.

The English language is pretty open to accepting new loanwords from other cultures, which makes it one of the most dynamic and versatile languages in existence. As such, the list of Japanese-origin words goes on and on. Some have taken on totally new meanings in America and elsewhere, such as Sukiyaki (a hot pot beef dish in Japan, a pop song in the US) or Hibachi (a brazier in Japan, a BBQ grill brand in the US), while most others retain their original meaning. In this post we highlighted some notable Japanese words that are not so obviously Japanese. How many did you know?

Douglass McGowan