In linguistics, “false friends” refers to words in two or more languages that are spelt the same or similarly but have different meanings. The term comes from Les Faux Amis, a book first published by French linguists Maxime Koessler and Jules Derocquigny back in 1928. Also known as “false cognates” and “treacherous twins,” these misleading word pairs can do a variety of damage, ranging from grins of embarrassment to failed business or diplomatic negotiations.

Words like “de” meaning “of” or “from” in Spanish and “the” in Dutch, “o” which means “or” in Spanish and “the” in Portuguese, or “or” meaning “gold” in French for that matter, are only minor irritants that pose little risk of miscommunication. The real danger is in word pairs that seem more plausible as carrying the same meaning.

In his research, Pedro José Chamizo Domínguez cited a minor diplomatic incident that happened after a conference delegate, whose native tongue was Spanish, gave a speech that was described by an English delegate as “fastidious” (in the sense of being “attentive to detail”). The response was less than warm. Why? Because in Spanish the word “fastidioso,” as does “fastidioso” in Italian and “fastidieux” in French, carries more of the negative nuance from the Latin root “fastidium” (dislike, disdain, disgust). In other words, the delegate thought his speech was being dissed big time. Imagine the awkwardness that permeated that room at that moment, brought to you courtesy of the false friends fastidious/fastidioso. It’s a good bet that people were embarrassed, which is not to be confused with Spanish “embarazada” (which means “pregnant”).

In other news, fans of the blockbuster drama series The Good Wife may remember the episode Foreign Affairs (Season 2, Ep. 20), where a bilingual clerk notices a mistranslation in a contract document, helping the lawyers negotiate a better deal for the client. The turning point was provided by the false friends exit/éxito. In the story, as the English base document was translated into Spanish, the term “Exit strategy” was erroneously rendered as “Estrategia de éxito,” which actually means “Success strategy.” Kudos for catching that one (even if it’s just fiction)!

These were just a few examples of the effects of false friends. Now let’s look at the causes.

Contents

Why do false friends exist anyway?

Unlike those previously unknown “friends” who mysteriously start showing up when you’ve got a winning Lotto ticket in hand, there are three real causes leading to the false friend phenomenon: Shared etymology, Homonyms, and Pseudo-anglicisms.

Shared etymology is just a fancy way of saying different words that come from the same common root. Overwhelmingly when an English word is false friends with another word in a Romance language, that’s because they sprout from the same Latin or Greek root. Likewise, when an English and German word look alike, it’s probably because they share an old Germanic ancestor. But along their way to their respective languages, their meaning diverged, sometimes subtly, sometimes drastically.

“Pasta” comes from the Latin word “pasta” (dough, pastry, paste), and through Italian it has generally come to mean “noodles” in the English-speaking world. But in Polish, “pasta” could very well be the short version of “pasta do zębów” (toothpaste). And while both English “celibate” and French “célibataire” come from the Latin “caelebs” (unmarried), the English term may imply abstinence for religious reasons while the French term simply means that a person is single.

“Zee” in Dutch means “sea,” but in German they say “Meer,” which is a false friend of Dutch “meer” (which means “lake”). This divergence happened because both “zee” and “meer” originated from words that meant “a large body of water.”

English provides an especially rich environment for shared etymology type false friends, as it is a Germanic language (Saxon) that was later infused with copious amounts of Romance language (Norman) vocabulary. So expect false friends in all directions.

Homonyms

Homonyms are words that look or sound the same, and in the sense of false friends this similarity is strictly by chance and not due to a shared etymological background, so their meanings tend to differ wildly. For example, a “gift” would not be welcomed by a German as the word means “poison.” “Barf” in Farsi means “snow” and is also the brand name of a laundry detergent. In German, “fast” means “almost” and “bald” means “soon.”

Japanese “saga” (habit) sounds the same as English “saga” (dramatic history) but share no common etymology. Meanwhile, “namae” in Japanese has the same meaning as “name” in English, but they’re etymologically total strangers who just happen to look similar (and therefore aren’t even homonyms in the true sense). There are lots of homonyms across languages, but for the most part they don’t pose any serious problem for the experienced translator (but can be very funny nonetheless).

Pseudo-anglicisms

Pseudo-anglicisms are new words formed in another language based on an English word or words, providing a new intended meaning. These would include the German use of “Beamer” for a video projector, “Dressman” for a male model, “Flipper” for a pinball machine, “Handy” for a mobile phone, and “Oldtimer” for an antique car. Also let’s not forget how the Danes refer to a minced meat sandwich as “Cowboytoast.”

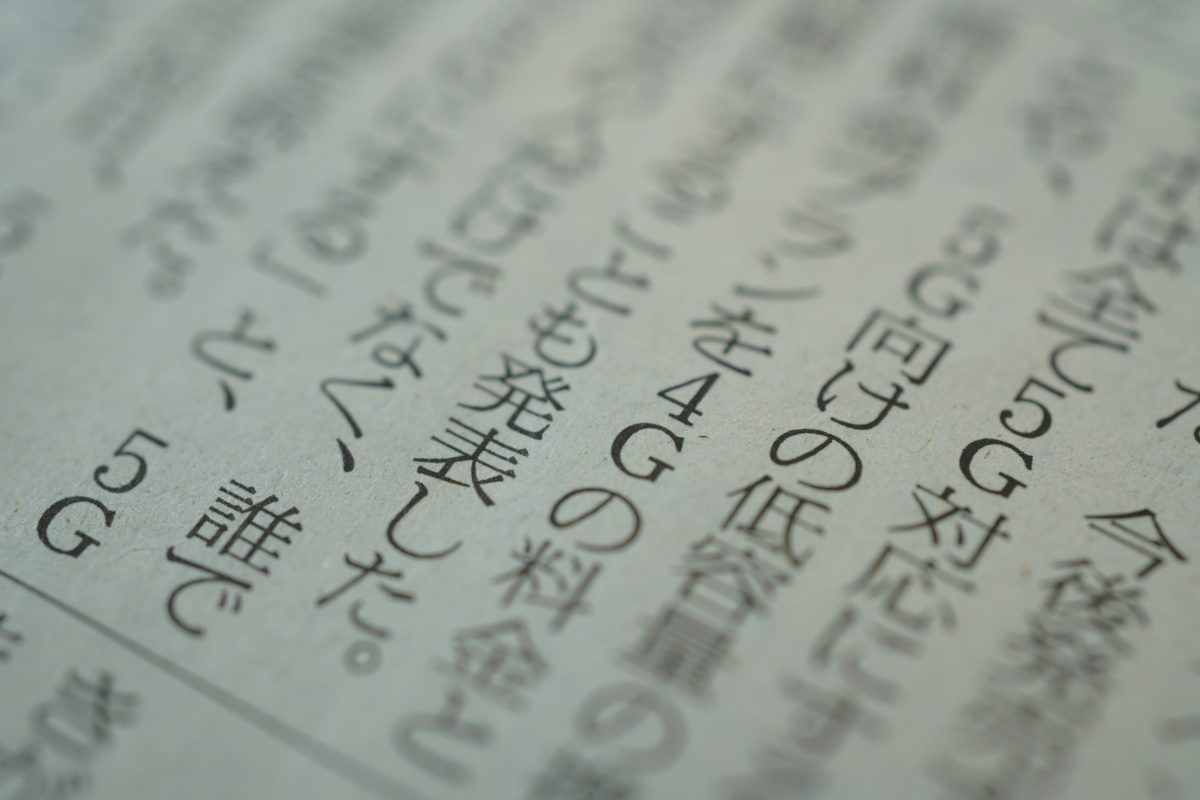

But when you look into the Japanese language you discover a whole new level of pseudo-anglicisms called wasei-eigo (English made in Japan) or Janglish, in which an office worker is called a “salaryman” or “OL” (for “office lady”), a stroller or pram is called a “baby car,” and in baseball, when a batter gets hit by a pitch it is referred to as a “dead ball.” But instead of getting into the details of wasei-eigo here, those who are interested can check out our blog post Breaking down Janglish: Japan’s unique take on the English language for a deeper dive. Suffice it to say that the challenge for translators is to make sure that a Janglish term does not make its way into an English translation as-is (some of them are subtle and mixed in with other loanwords that do carry the same meaning).

Safeguarding against false friends

Fortunately, modern localization workflows include safeguards against false friends and other mistranslations through the use of TM (Translation Memory) and LQA (Language Quality Assurance) steps, including double-checking by a reviewer. Such workflows help ensure that false friends do not wreak havoc in your text documents. The challenge lies more in tasks where TM is largely irrelevant, such as subtitle translation, and even more so in the field of interpretation.

Interpretation, whether in-person or remote, is more susceptible to false friends due to the immediacy and time-critical nature of the work, in which human error has a higher chance of materializing. However, and in a way luckily, interpretation has a very short shelf life. Transcripts may remain, but for the most part, people are quick to move on beyond minor misinterpretations as the flow of words continues and time refuses to stand still.

Douglass McGowan